Jutland’s Textile Heritage

The Danish region of Central Jutland, or Midtjylland in Danish, is known for its textile industry. Nowadays, it is host to global companies such as Bestsellers (which includes Vero Moda and Only, for example). But did you know that this is deeply rooted in the region’s history and geographical characteristics?

Thanks to Aarhus Universitetsforlag, I received a copy of Kristine Holm-Jensen’s new book ‘Uldjydens triumf’. Tough to translate but it roughly means the ‘Triumph of wool(ers) of Jutland’. Not only was it the first book in Danish I ever read from start to finish, it is also the first book about the textile industry I thoroughly enjoyed. Uldjydens triumf is a case study of industrialisation through the lens of wool, textiles and fashion with a focus on Denmark, particularly Central Jutland. The industry changed society and vice versa, which I loved learning about.

Short history

While farmers would often bring their knitting during their days out with the herd, spinning was done at home, often during the quieter winter months and mostly by women.

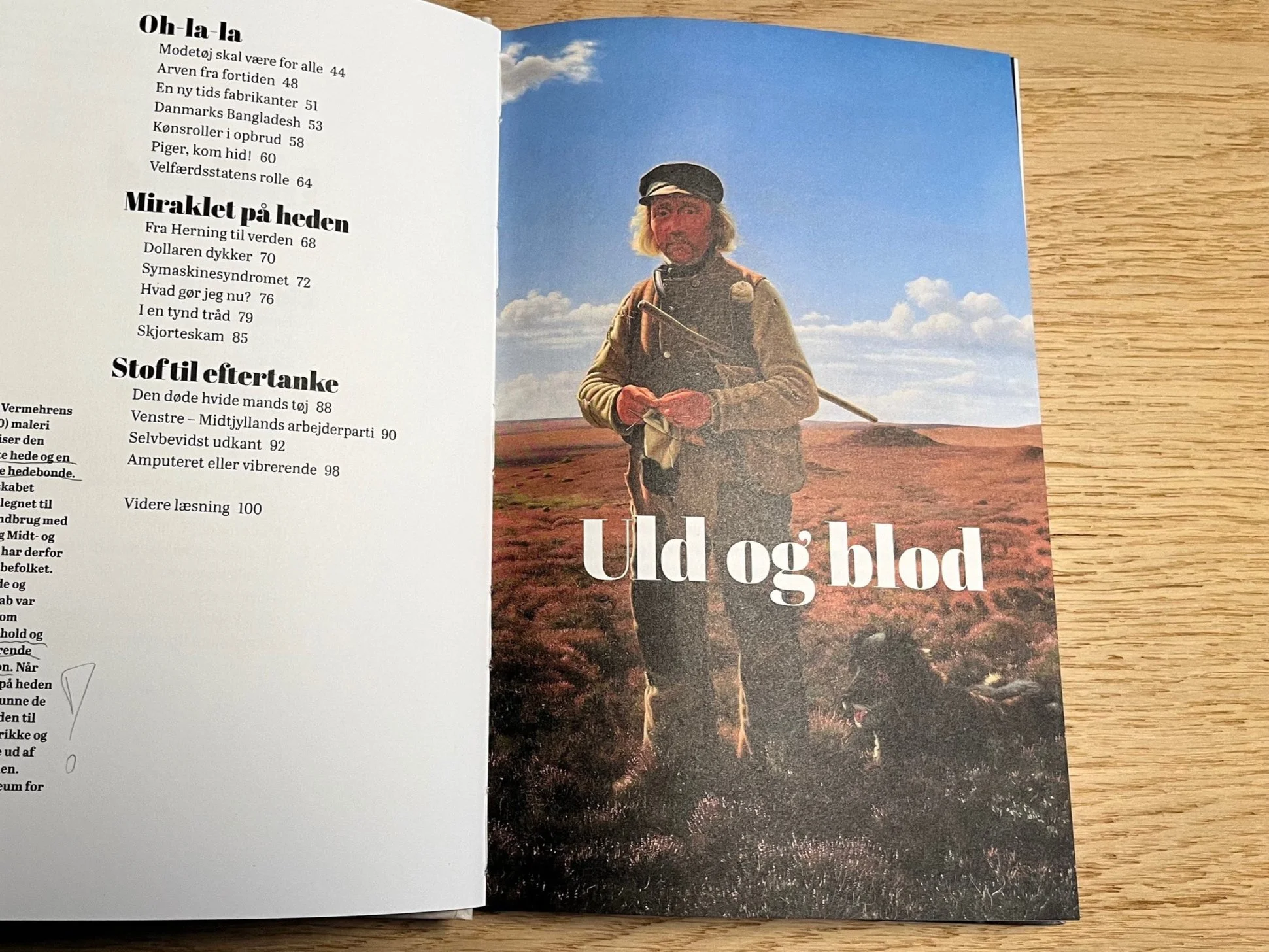

Central Jutland’s landscape is flat, vast and not very suitable for farming. However, this makes it perfect for sheep, who can find food regardless. Knitting first came to Northern Europe around the 1500s, and it was landowner Christian Rantzau (of Herningsholm), who saw possibilities to use sheep herds for wool production in 1627. From the 1700s, the trade with Jutlandian wool products started, especially towards Copenhagen, and flourished during the following century, which is when the term ‘uldjyde’ came up first.

The second half of the 1800s brought industrialisation and with it train lines connecting cities and towns as well as machines revolutionising tasks previously done by hand. The first sewing machine entered the Danish market in the 1860s and could sew 300 stitches per minute. For comparison, a good hand sewist can sew about 30 and an industrial machine nowadays does up to 5000. Factories were opened in Jutland producing knit and woven fabrics as well as ready-to-wear clothes later on.

While Denmark struggled post the Second World War, the Marshall Plan aimed to modernise industries. For the textile industry in Central Jutland, this meant more a specialised production with standard sizes and patterns, instead of the personalised approach tailoring workshops would provide. These efforts led to decreased production costs and sales prices, which in turn increased production and sales.

Society changes and women’s roles

Seamstresses dance jazz ballet in a factory in 1964.

Clothes had become affordable to everyone and class lines - previously apparent in clothing - disappeared. Additionally, the shift from the (over)shirt to t-shirt shows society’s wish for something more versatile with a simplified construction. Knitwear and -fabrics were also cheaper and this played right into Central Jylland’s knitting traditions.

One thing that I cannot forget after reading the book was on page 58. Since sewing was traditionally a woman’s job, it was almost exclusively women being hired in factories of the 1950s and 60s as seamstresses. However, the author describes that women were simply the cheaper workforce as the equal payment act was only passed in 1976 in Denmark. What struck me was the blatant admittance of this fact. I am so used to having to debate pay inequality today that this made me stand in awe of the first women pushing into the workforce at that time.

With women entering the workforce and earning their own living, society and with it gender roles changed. Young women would, for example, spend their first income on a driver’s license - easing their commute and just generally giving them more freedom. It was also the development of the Danish welfare state and the provision of childcare enabling this change.

Sustainability and into the future

In Ghana, the used clothes arriving are called the Obroni Wawu: The dead, white man’s clothes.

Kristine Holm-Jensen takes the reader on a journey both through time and Central Jutland, where we meet factory owners, seamstresses and tailors. For examples, we get to follow Regnar Bøgsted (1921-2012), who following his dad’s (well-intentioned if somewhat wrong) recommendation, that there will always be a need for tailors, did his apprenticeship and different jobs, before he started his own workshop in Herning in 1945. The description of his work and day-to-day life reminds me of a recent interview with Patrick Grant on the Love to Sew podcast. The glaring commonality is the long durability of a well-tailored suit and the sustainability that goes with it.

The industrialisation and growth of fast fashion have adverse effects on workers’ health as well as on our planet. Kristine Holm-Jensen does not shy away from showing the negative impact Western overconsumption has, such as the used clothes mountains on Ghana’s beaches.

A region’s DNA

To be honest, I didn’t know how textile-savvy Central Jutland was and how the triumph of the textile industry there can be linked to Germany’s automotive industry. Uldjydens triumf shows how the region’s great past in wool production is knitted into its DNA. While the book focuses on the history, Kristine Holm-Jensen manages to weave in and elucidate the culture and personality of Central Jutland and its inhabitants. It shines through each chapter and I learned just as much about the difference between Copenhagen and Jutland as I did about the textile traditions. A well-rounded, interesting read, if you are into any of these topics.